Page Content

Teaching, to me, is a paradox, an amusing mixture of joy and pain. It’s a profession rooted in interactions and the building of relationships, and while these relationships are typically a source of tremendous satisfaction, they can also bring gut-wrenching heartache.

When I was in my sixth year of teaching, I transferred schools, moved to a new city and started over. This is when I met Jack, a new student in my English 20 class. Little did I know he would change my life forever.

Jack was pleasant enough, at least as pleasant as surly teenage boys are able to be in the morning, and was by no means difficult. But I could tell from his strained interactions in class that he was struggling to fit in. I could empathize, for new schools can be tough.

One morning, I noticed that Jack appeared especially gloomy, keeping his head down and paying no particular attention to the proceedings.

“Jack, could you please lift your head and join the class?” I said, not thinking much of it.

What happened next was like one of those moments in the movies when the camera shifts its focus and tilts. Jack hurled a lengthy list of expletives in my direction that included a threat to end my life, then stormed out of the room and slammed the door, knocking the phone off the wall and the breath out of my chest.

I spent a few minutes getting the class settled, then contacted the office about what had happened and to see if Jack had made it there. But, of course, he had not gone to the office; he’d left the building.

The situation escalated from there. After leaving the school, Jack had returned to his house and retrieved a weapon. The police were notified and were quick on the scene. Due to Jack’s threat toward me and concerns over what could happen next, the school went into lockdown.

We had practised a lockdown drill several times, but a real one feels entirely different. It was tense. Some students were curious as to what was happening; some had heard in the hallway what had happened in my class. As the time dragged on, our collective patience waned. Then, more than three hours later, the lockdown was lifted and we learned of Jack’s suicide.

Things moved very quickly at that point. Announcements were made, staff and grief counsellors gathered in the staff room to hear the events of the day, and I was quickly shuffled into the office to debrief the day. It all seemed surreal. People, noises, conversations swirled around me as I struggled to make sense of what had happened.

This remains the darkest day of my career and the moment when everything changed. I thought I’d been in control, but control is deceptive. I felt that, if I’d been in control, Jack would have not taken his life.

This incident sent shock waves through our school. The district’s emergency response plan was implemented, allowing for counselling for all students and staff. Teachers are expected to be steadfast in times of crisis and help students with the immediate impact of traumatic situations, and that is exactly what we did. We were taught the signs and symptoms of students struggling with the aftershocks of the lockdown. The media attention died down, the wealth of counsellors returned to their respective schools, and our normal routine of bells and classes resumed.

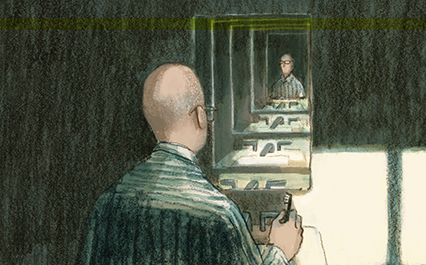

Following “the incident,” as we called it, staff were well-supported in the short term, but as the year progressed, a wall of silence grew around it. While others in the school moved on, I remained stuck, reliving a nightmare I could not contain nor change. I was devastated by the loss and began to lose the sense of self and confidence that I had acquired throughout my early career. Over the course of several months, I struggled and faltered, exhibiting characteristics of post-traumatic stress disorder. I was quick to anger, had little patience, felt numb and carried a tremendous amount of guilt over what had transpired. Several months after the incident, I caught myself staring blankly into the bathroom mirror, brushing my teeth for close to 45 minutes.

I believe there are two types of people in the world: people who own their problems and those who are owned by their problems. I realized in that moment that I was owned by the loss of Jack. I was carrying the weight of his suicide, and it was crushing me.

I knew had to get myself back to a new sense of normal. Recognizing this was not a journey I could manage alone, I sought counselling assistance, and I was fortunate to have administration and staff who supported my recovery. I was not made to feel weak, broken or incapable.

I worked hard through therapy to recapture my inner self. It allowed me time to reflect, think, heal and eventually forgive. I forgave myself and laid down the burden of his death that I had been carrying. I became a different person after the incident as I came to realize that we do not have control over all aspects of our lives. I became more present in my life with my students, friends and family. I like to believe that I became a better teacher through the coping strategies I developed. I realized that it was okay to talk about what I was going through, it was okay to seek the help of a professional, and it was okay to not be okay.

This experience has framed my thinking around trauma and was the catalyst of my master’s work. Trauma can have a huge impact on teachers. My career did not end after the suicide of my English student, but it could have. I think about Jack often, and I am sorry that we failed him. Losing Jack made me find myself, made me a better teacher, a better colleague and ultimately, a better person.